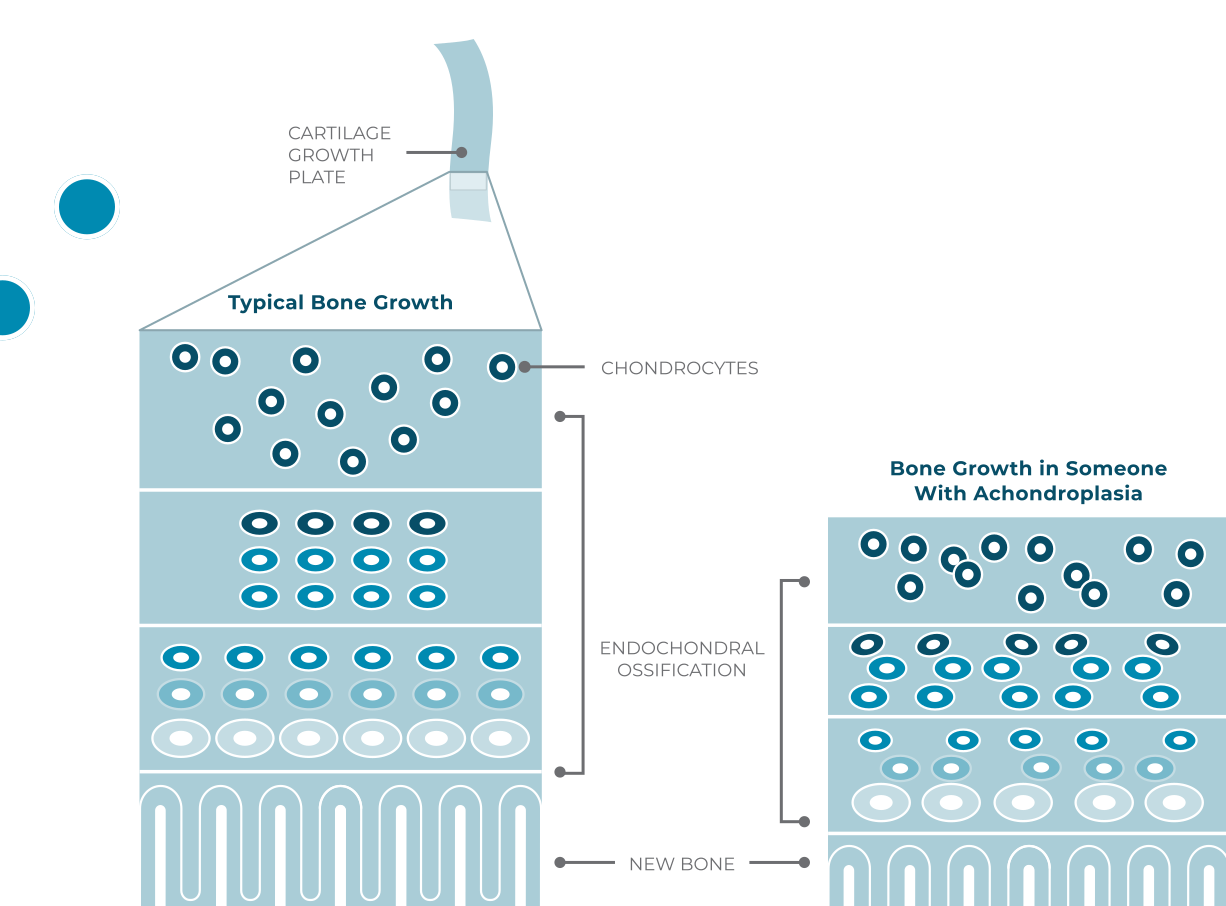

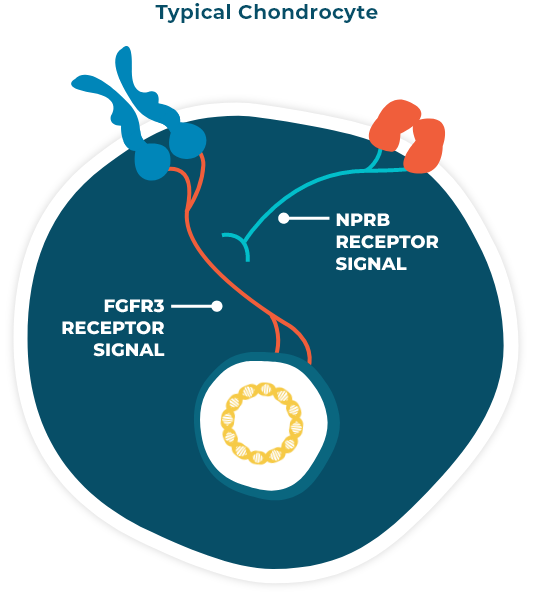

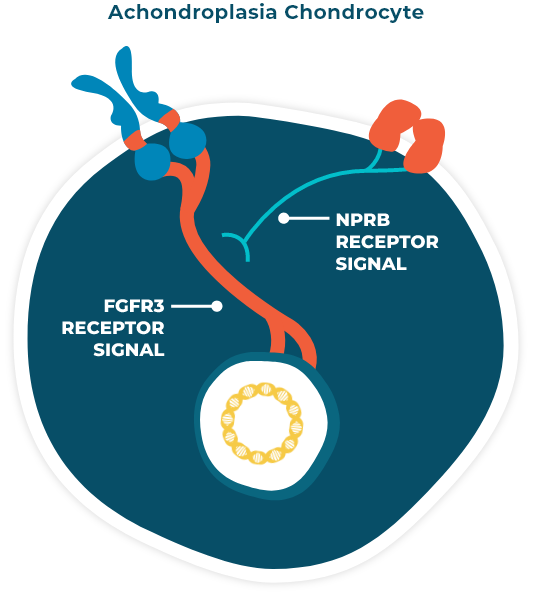

Achondroplasia is the most common cause of short stature, or dwarfism. One of the most important things to know is this: it’s about more than just height.

ACHONDROPLASIA IS

RARE

GENETIC

DIAGNOSED IN DIFFERENT WAYS